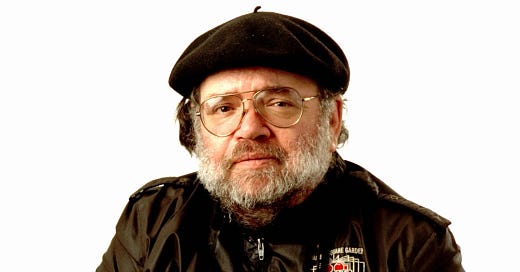

He was irascible and opinionated, wore a beret and a beard, and was one of the best boxing reporters in the business.

Men in the boxing writing business had their own language and their own stories. Sometimes, they fought. And then made up. I was the only woman on the beat at that time.

Mike Katz stood up for me and gave me two great pushes that propelled my career forward. I have never forgotten.

Boxing, like baseball, has its own writing association. My application was denied by Barney Nagler, then president of the Boxing Writers Association. But I had similar credentials as the men, as a working writer for El Diario-La Prensa. I mentioned it to Mike while we were in the press lounge at Madison Square Garden back in the 1980s. He called over Nagler, always dressed in a suit and a tie.

“What are you doing?” he demanded. “She deserves to be here.”

My official card was mailed that week. I may have been the first woman in the Boxing Writers Association, I don’t know, but he listened to Mike.

Michael Katz is pictured in 1996. (Pat Carroll / New York Daily News)

Later, Mike who sometimes called me kid, and I would travel by bus together from time to time to Atlantic City when he covered boxing for The New York Times and then the New York Daily News. Phil Berger, the Times boxing writer, who died at a young 58, was a better traveling companion because he had a car and sang Frank Sinatra songs.

Mike, who was over 20 years older than me, turned as we waited in line for the bus.

“You’ll never be a success,” he said. “You don’t drink, you don’t smoke, and you don’t chase women.”

I’m not sure what I said. Probably rolled my eyes. I can picture us standing there outside with our coats on, waiting to board for a press conference or a fight at one of the casinos.

I was often moving around doing my own thing so I didn’t sit ringside with him and the other beat writers.

Once, our seats were next to each other at the Beacon Theater, two chairs behind a wooden plank facing the ring with touch tone telephones on the table. Stories were transmitted through the phone line and connected from your Radio Shack laptop. As we settled in, he picked his phone and threw it back down.

“This fucking thing isn’t working,” he fumed. He was boiling and pacing.

Picking up the receiver on the phone assigned to me which was to his left and then the one to his right, I found that they both had dialtones.

“Mike,” I said, “Just switch the phone with the one next to yours. Then it’ll work.”

He stopped short. This was the only the second time he was silent.

The first time, a newspaper strike at the Daily News in 1990 put him on the picket line. Someone from the Daily News called and asked if I wanted Mike’s job.

“Thank you for asking but no,” I said. “I’m not crossing the picket line.”

Mike once lashed out at a colleague, his words so angry, so bitter, so uncalled for. The man turned to me, in tears.

“What did I say?”

I assured him that he did nothing wrong, let it go, he’ll calm down, keep it moving, maybe a bad day.

His worst day. Mike’s wife, Marilyn, died of breast cancer in 1990. She was only 37. They had one daughter, Moorea, named after the island in French Polynesia where she was conceived. I don’t know if he took time off from his work to mourn. I doubt it.

He didn’t have to speak of his grief. The sadness, buried under his beard, beret, and a neck brace, was painfully obvious.

When I was laid off from El Diario-La Prensa, Mike rescued me. He placed a call to the sports editor, Joe Vecchione, freelance assignments, most of which I initiated, came my way. Sometimes, I had more stories in than Phil Berger but Phil didn’t view me as competition, only a colleague.

Without Mike’s phone call, I would not be where I am today.

We had a falling out, one of those man-woman things. I wanted to keep our friendship professional. I approached him several times. He glared at me and moved away, furious. I tried calling. He hung up the phone.

Moorea, his daughter, died of breast cancer at 39, the same disease that killed her mother, in 2021.

I didn’t call him. I was afraid, even after all these years, that I would be rebuffed again.

Michael Katz died this week at the age of 85.

He has a son-in-law and a granddaughter, Beatrix. If the kid needs anything, I’m here.

Arlene, beautiful. That was Michael. His yin and yang were both monumental.

He was a dear friend and talked that talk like my husband Vic Ziegel.

Thank you. Roberta Ziegel

Roberta, thank you! I remember meeting Vic. What a mensch. I remember that he and Mike were close friends and that both attended City College. May their memories be for a blessing.