Another wind of memory carried me to the steps of my aunt’s Bronx tenement building on University Avenue and Kingsbridge Road.

“Those bastards!”

Auntie Esther shouted through the apartment door as I fumbled with her keys in the old lock. She wasn’t really my aunt but my grandmother’s sister so this made her my great-aunt. I squinted both eyes in the dim hall light and felt around for the lock. The sounds of Hawaii 5-0 reruns reverberated into the hallway of her old six story high dirt brown brick building. It was so loud I thought Jack Lord was standing next to me.

Two Puerto Rican teenagers clumped down the hallway stairs in their heavy boots and thumped basketballs against the steps and walls. There were no elevators in her building, just two large stairwells at either side of the building that neighbors had climbed up and down for decades. I winced as bounces echoed off the walls but the boys ignored me in the shadows, another home attendant, they figured, coming to call on the building’s elderly.

I shoved the heavy door open and almost bounced back into the dark and musty hallway from its weight. A heavy police lock held the door, a brass bar stuck a hole drilled into the floor and inserted into an oval brace on the back. After wedging myself through the opening, I held my stomach and my breath and pushed myself in. I yanked my pocketbook in after me with a few sharp tugs. I dusted myself off and slammed the door shut. This painful routine would be played out in reverse when I left.

“Hello, Auntie Esther,” I called out. “Hello. HELLO. AUNTIE ESTHER, I’M HERE!”

She stared intently at the TV screen. She didn’t notice me until I stood in front of the blaring television, waving my arms like a fan at a Giants football game.

“HELLO, AUNTIE ESTHER!”

Auntie Esther sat in a sagging armchair purchased as part of a living room set back in 1959. The two chairs and couch were champagne colored weave protected by thick plastic slipcovers, owned by every member of her generation. I once poked a small plastic hole in the couch plastic—the almost half century old fabric was just like new. The armchair had seen better days; the plastic was gone, the armrests were thin and bony with fabric worn away.

“Those bastards!” she shouted again from the living room.

She once sat blissfully on her perch like a pear shaped bird covered in polyester, looking at her TV while a three-alarm fire blazed in the apartment next door. Three fire trucks pulled up, dozens of firemen with acres of hoses began dousing the flames. Police cars with their sirens on alerted neighbors. Fireman, cops, and neighbors banged on her front door and rattled her windows.

Finally, a fireman broke in the window gate in the bedroom to rescue her. “Who are you?” she demanded.

“Here”—she reached under her chair cushion to retrieve her purse and offered him—“Take these two dollars, mister, and go out the same way. I have no more.”

Thankfully, there was no damage to her apartment, Auntie Esther, or the chair.

When Auntie Esther finished reading her mail, she would stick the letters and bills under the seat cushion and sit on them, the papers and envelopes sticking out like a large fan. From that chair, she successfully bullied the telephone company into reducing her $22 bill by three dollars, bossed around home attendants who didn’t make her tea hot enough, and was examined by visiting nurses who took her blood pressure while she would say, “You know, I’m not so young anymore.”

The nurse would pat Auntie Esther on the arm, “You’re doing fine, Mrs. Nachman”, and she would cheerfully reply, “I had that for lunch yesterday.”

Now she turned to look at me.

“Oh, hello, Arlene,” she said, as if she had just met me on the street, a casual acquaintance rather than her favorite niece. She cleared her throat and coughed twice, as was her habit.

“What did you bring me?” she would inquire, not pausing for my answer and staring at me without blinking.

“I don’t think you love my anymore. Why weren’t you here yesterday? They’re trying to rip me off. Those bastards. I didn’t have it easy. Nobody ever comes to visit me. Think you’ll see me before I die?” she added with a nervous laugh.

I groaned. I had only heard this five times a week for the last three years. Moving to turn down the TV, I was intercepted by 50 years and two hearing aids.

Auntie Esther was actually softer than she sounded. She wasn’t skinny and shrill with bony fingers but rather lumpy in a faded housedress. Her gray hair was cut short and felt as soft as old cotton. Her skin was soft, too, and pink without wrinkles, and if she had a makeover and a sharp outfit, at 90, she could pass for 60. In her younger days she was blonde and blue eyed. Her eyes looked the same but without her false teeth, I didn’t recognize her.

“Scared you, didn’t I?,” she always said with a laugh when she took them out at night.

Auntie Esther lived in the same one bedroom apartment for over 25 years, on the first floor, a half block in from Kingsbridge Road on University Avenue and not far from the elevated subway on Jerome Avenue. Her rent was $88. Her one kitchen window, two living room windows, tiny bathroom windows, and one bedroom window all faced the courtyard. Everything was painted chalky white, the same cheap paint landlords all over the city have been using for generations. Her carpet was a faded green tight wool weave, nailed to the floor, and impervious to removing. I don’t think she ever washed it but used a metal carpet sweeper to pick up her crumbs. She didn’t have many.

Auntie Esther left her apartment every day to eat lunch at the nursing home across the street. Sometimes I would find an extra package of graham crackers or a piece of fruit wrapped in a napkin in her refrigerator. The neighborhood had changed from Jewish and Greek to Puerto Rican, Dominican and West African. Elderly Jewish women were still scattered throughout the buildings on University Avenue and Kingsbridge Road, always looking out from apartment windows wearing sweaters in August. Some lived alone, others lived with home attendants, and a few never came out anymore. Kids hung around corners and in front of buildings while my aunt sat on a green wooden park bench on a traffic island inhaling bus fumes and watching the traffic go by in the midday sun. She spent her days walking around the neighborhood, past the abandoned armory on Kingsbridge Road, pizza places, bodegas, and hardware stores, looking to save five cents on a loaf of bread, three cents on a package of cream cheese.

The only time she left her neighborhood was to purchase batteries for her hearing aid from a doctor on the Grand Concourse or to meet her younger sister, Mollie, and her cousin, Betty, when they made their annual pilgrimage to see Liberace at Radio City Music Hall. To Aunt Mollie, who lived in a one-bedroom room house in Deep River, Connecticut so small we called it a dollhouse, Liberace was a god. She and her bridge-playing gals looked forward to the trip every year. I think everyone knew he was gay except for them. And it was a good thing because my aunts probably wouldn’t have approved. By the time he died and his lifestyle exposed, Aunt Mollie had developed Alzheimer’s.

“What are you doing to the television?” Auntie Esther squawked at me. “Now, I can’t hear it. I want to go down and tell those people at the telephone company who are charging so much —those cheaters. How can they do this to an old lady? I don’t know why they do this to me,” Auntie Esther complained, buttoning an old white acrylic sweater with two buttons missing.

After fumbling with the knob on the television, I finally turned it off and sat down on the plastic sofa. My bare arms stuck to the plastic.

She shifted her weight and pulled a white piece of paper from under the seat cushion of her throne.

I unfolded the paper. It was her Con Ed bill.

“What’s the problem?”

She didn’t hear me.

“WHAT’S THE PROBLEM?”

“The telephone company is trying to rip me off, those bastards. I’m an old lady living here. Why is this bill so high?” she complained. “I’m going down there and speak to the lady in charge! This never would have happened to me if I had children!”

I rose wearily from the fusillade.

“How much is the bill supposed to be?” I asked, looking around her card table for the telephone bill. She sat like a bird defending its nest, so there was no way I was going to reach for it under the seat cushion.

“WHAT DID YOU SAY?” Auntie Esther shouted. “Who’s at the door?”

“WHERE’S THE BILL?” I shouted back.

“Why are you yelling?” she replied grumpily, reaching under her left hip for the bill and handing it to me.

The bill was $22.32.

“Uh, Auntie Esther, AUNTIE ESTHER,” I shouted, standing next to her so that she could hear me. “LOOK AT THE BILL! THIS IS CALLED INFLATION! EVERYONE’S TELEPHONE BILL GETS LARGER THE MORE TELEPHONE CALLS YOU MAKE!”

I remembered using the telephone during my visits, including calls to my home to check my answering machine.

“AUNTIE ESTHER, THIS IS NOT A LOT OF MONEY!”

“Sit back down on the couch,” Auntie Esther ordered. “I want to tell you something.”

I looked over at the couch and cringed. The living room windows hadn’t been opened in years and she refused to turn on the air conditioner in the bedroom because it cost too much money. Beads of perspiration formed on my forehead as I looked over at the plastic slipcovers. “You could fry a chicken on this thing,” I mumbled to myself and sat down.

“Dorothy,” she said, “Sonia-Stephanie-Laurie— ”. As a kid, I thought I had many names. Every female relative of mine would trot through everyone else’s name before we addressed the person in front of us. There weren’t that many of us and we don’t look anything like each other.

“—Anna- Ah-lene,” Auntie Esther concluded, without apologies, clearing her throat and coughing twice. “Get me some ginger ale from the kitchen. Use the glass on the sink and not too much. Take some for yourself.”

My legs left the sticky plastic with a squeaking noise and I found a glass in the kitchen. I poured the ginger ale and put the opened can back in the refrigerator next to a sad looking glass bowl crowded with four hard-boiled eggs.

I put two paper towels under the glass and walked back into the living room with a sigh.

“Here you go,” I said, sounding weary than cheerful. I knew it was going to come sooner or later.

Before she took a sip, she counted the paper towels.

“Why are you giving me two?”” she blasted.

“That’s what came off the roll,” I explained, sitting back down, this time on the edge of the couch.

“Why did you give me two?”

“Next time, only give me one. Go take some for yourself.”

I rose from the couch and poured myself a glass of ginger ale from the kitchen, the cool, sweet drink a welcome relief from the temperature inside the apartment.

I excused myself to use the bathroom and to splash cold water on my face.

"Make sure you turn on the bathroom light,” Auntie Esther warned me. I groaned.

“No, I’m going to sit here in the dark,” I muttered to myself.

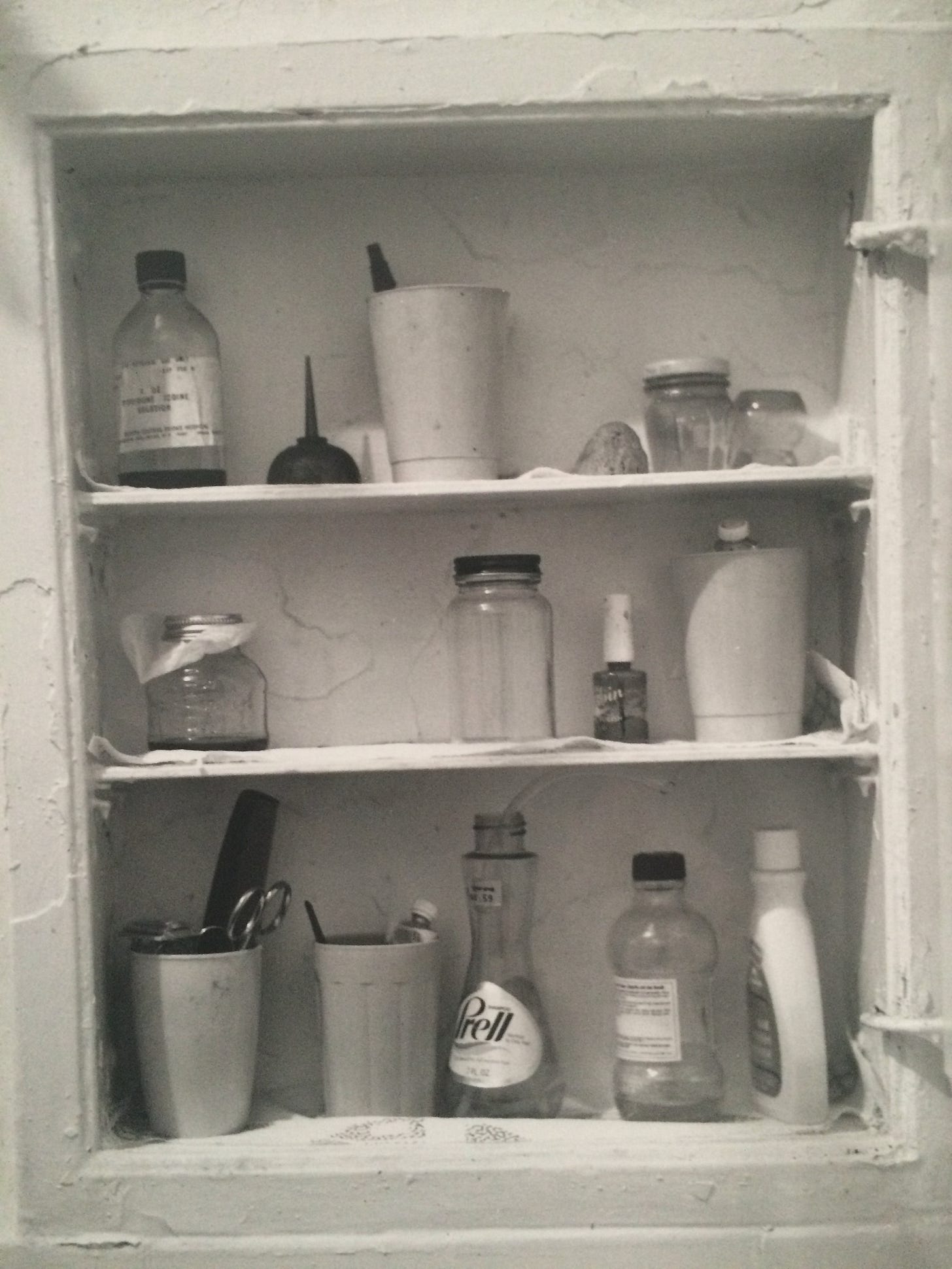

As I fished around for the end of the roll of toilet paper, I noted that Auntie Esther washed her clothes by hand in an enamel bathtub, the water emerging from a circular hairbrush style faucet suspended from a ceiling pipe. It looked like a set from an early silent movie. The apartment hadn’t been painted in at least fifteen years but since Auntie Esther didn’t wear her eyeglasses, it all looked in mint condition to her.

Opening the bathroom door when I had finished, I found her staring at the door as I made my exit.

“Make sure you turn off the light,” she told me. I groaned and turned off the light.

Auntie Esther looked at me. “You’re getting old,” she sniffed.

“So are you,” I replied.

I looked at my watch.

“Auntie Esther, I just checked in to see how you’re doing. I want to know that you’re all right. But I can’t stay,” I told her.

“WHAT?” she shouted.

“I CAN’T STAY!”

“Why? Do you have a date?” she inquired with a chuckle. “Get one for me.”

“I HAVE TO GO! I have work to do at home. I’ll see you next week,” I said, grabbing my pocketbook and moving the police lock to scramble out.

As soon as I turned the key in the lock of my apartment door, the telephone rang. The answering machine turned on before I could reach the phone.

“Cough, cough. Hello (pause) Arlene. This is her Aunt Esther. Tell her to call me when she gets home. Did you hear me? Okay? Thank you.”

I wished I had saved the tape from the answering machine so I could hear her voice again.

Auntie Esther lived as a relic from another era, one of those elderly Bronx women you’d see walking slowly with a cane, wearing a faded housedress, pink sweater, and old knitted cap and standing out as a stranger in a neighborhood that changed faces a long time ago. The world outside of her University Avenue apartment shifted not so subtly, but she didn’t. Plastic slipcovers, wooden furniture from the fifties, vintage dishes and clothing, an old television with rabbit ears. . .visiting her was like viewing an exhibit preserved at the American Museum of Natural History.

Her building neighbors spoke Spanish, not Greek and Hebrew, and they left the hallways perfumed with the scents of chicken and rice and beans and fried fish. One by one or two by two, kosher butchers in the Kingsbridge area closed, and she traveled further and further, sometimes taking three buses for a round of hot dogs or chicken. Auntie Esther stayed her course until she fell and broke her hip. She decided how she was going to live and most stubbornly, how she would die.

Her neighbor telephoned me when she fell in her apartment and luckily and thankfully, I happened to be home. Auntie Esther didn’t call the generation between us. My mother was living in San Francisco and my aunt was living in Co-Op City but I lived across the Fordham Bridge in upper Manhattan, visiting every so often and telephoning to check in and say hello.

The second oldest of five Greek sisters, Auntie Esther had been divorced once, married twice, and was now a widow. She had no children. Her oldest sister had married a man in the film business, moved to Harlem, and died in the 1918 flu epidemic. The next was Stema, who died of breast cancer more than 20 years ago. At the time of this writing, the youngest, Mollie, lived in a nursing home in Connecticut and didn’t remember anyone, even though Auntie Esther insisted that she did. Mollie had Alzheimer’s. My grandmother lived in another part of the Bronx and was in her early eighties. So there I was.

Auntie Esther was 88 and I was 28. I knew almost nothing about growing up and growing old, only that it happened to other people.

My writing and photography career was in full swing. But After Auntie Esther’s telephone call which led her — and me — to two hospitals, a rehab facility, and then home and back again, I went from deadlines, knockouts, hits, champions, and home runs to hospital procedures, high blood pressure, elder care law, diuretics, physical therapy, broken hips, pneumonia, wills, assisted living, health insurance, Medicare, social services for the elderly, home health care, feeding tubes, ventilators, social workers, living wills, nursing homes, funeral homes, plain pine boxes.

The rest of my family remained in the background, a polite way to say that they weren't interested or didn’t know how to be. Almost every member of my circle of friends, colleagues, and acquaintances hadn’t yet encountered aging and ill parents or grandparents or to put it bluntly, the death of a family member. With perplexed sympathies and little support except for “You’re doing a nice thing," it was a solitary endeavor of love and obligation for almost six years. A geriatric caseworker filled some of my roles for about a year, until Auntie Esther didn’t like her anymore.

While she recuperated from surgery, I attempted to organize, paint, and clean her apartment, and ensured that her medical paperwork was in order. Auntie Esther knew what she wanted. When it was her time, she did not wish to be resuscitated.

“No. Just let me go,” she said.

She repeated herself so that I would hear, even though she was the one with the buzzing hearing aids.

She signed a DNR form in the hospital, which meant that if any measures were needed to keep her alive, she didn’t want them.

After several years living at home, it became clear that that she couldn’t stay in her apartment. Frustrated, fearful, and confused at times, she made hysterical telephone calls to 911, telling the operator to get her out of here. The very patient home health care worker we hired was drained, Auntie Esther was in and out of the hospital, and I was on the verge of collapse. During her latest hospital stay, I discovered how cruel it was to be in the hospital alone. A process called “dumping” meant that a patient without family was transferred to a waiting nursing home so that the bed was opened up for the next casualty of age. A representative from the New York City Department for the Aging explained how it worked. I telephoned Auntie Esther’s social worker at the hospital and demanded an answer.

“Don’t I have a say in this?” I asked. “Why did no one call me? My name is on the paperwork and I’ve been there to visit. This isn’t going to happen.”

The social worker seemed taken aback, as if I were ungrateful for her services. I called the New York Health and Hospitals Corporation who called the hospital and well, it gave me an extra day or two. The social worker, annoyed, offered two choices of nursing homes and I visited the original one first. A room filled with elderly women wearing pink acrylic sweaters sat lined up in front of a television that wasn’t turned out. The air smelled like urine. I whispered to a man mopping the floors.

“Would you send your mother here?”

He shook his head.

Nursing home number two wasn’t far from where she lived. I was running out of time before she would be discharged, and thankfully, it seemed much less depressing and with better services. Paperwork was filled out and so was a DNR form.

Auntie Esther was now 94. She hated the nursing home, hated her roommate, hated the food, and hated me. I was drained mentally and physically from rounds of meetings and telephone calls, emptying and cleaning her apartment, moving her in to the nursing home, traveling, negotiating, being yelled out, bureaucracy, and paperwork while continuing to work as a journalist.

She was living in the nursing home for less than a year when the telephone rang. She had been taken to the hospital. I asked about the DNR form. No one could find it. I dutifully went in and filled out the paperwork with her again. Auntie Esther was angrier than ever that her wishes had not been followed. I shook my head. I had no answers.

I spoke with the nurse: It should be in her chart. Was it a mistake? Did they lose her paperwork? Was this the mistake of a newer employee? Auntie Esther continued to yell, her hearing aids not picking up that I had nothing left but apologies. I remember walking away out of frustration. Nothing could go right.

Several weeks later, the telephone rang again. Again, she was resuscitated. I dutifully trudged to the nursing home, bracing for the barrage.

“Why did you do this?” Auntie Esther screamed at me.

I shook my head. My parting mental photograph is of her sitting in a wheelchair yelling at me as I retreated. The form was filled out again.

I was almost down for the count. And the phone rang again. She was taken to the hospital. And resuscitated once again. Auntie Esther sat up in the hospital bed with a large plastic tube in her mouth, her eyes unblinking in anger. If she could have yelled at me, I’m sure she would have. It was like a horror movie.

The doctor informed me that her kidneys were failing, and he spoke about withholding food, what he could and couldn’t do. I made calls to medical ethicists so that I could make a decision and it left me more confused. I had no idea of what to do, of the capabilities of the human body, what dignity she had left. It all seemed so unfair. And then the phone rang.

This time, she had her wish.

This story was written for my blog back in 2011 and 2013 and combined two stories. It’s been edited slightly. I think of Auntie Esther often. Her old Singer sewing machine is now in the museum of Kehila Kedosha Janina, a synagogue devoted to Romaniote Jews from Janina (Ioannina), Greece. She was born in Greece, the third of five sisters, and raised on the Lower East Side. Her education lasted through the fifth grade. Auntie Esther worked in garment factories to support the family before she married. She suffered through an arranged marriage from a man who cheated on her, had a happier second marriage to a widower, Matathia Nachman. His family was also from Janina. Her stepdaughter, Mollie Nachman, was murdered in their apartment by her boyfriend. Auntie Esther found her stabbed to death in her bed, which haunted her for the rest of her life.

RIP Auntie Esther. You are always in my thoughts.

Thank you so much!

This is so vivid and so moving. Many of the details bring back people, and plastic-covered furniture, of my youth. You were a blessing to her. May her memory be for a blessing to you.